Overview

- This paper will consider double taxation treaties as they apply to the treatment of capital gains particularly by reference to Burton v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCAFC 141; 372 ALR 193 (“Burton”). Whilst the case of Burton is a judgement of what the law is, the Federal Court does not comment on what the law should be.

- In my view, as a result of Burton section 770-10 of the ITAA 1997 has become an example of failed international taxation policy and a failure to prevent double taxation. In this paper I will consider:

- the purpose behind laws which seek to prevent double taxation;

- a discussion of the Burton case and in particular the court’s reasoning as to the application of the relevant double taxation treaty to his income (which was taxed in multiple jurisdictions);

- a consideration of whether applying the facts of Burton in other jurisdictions, such as Canada and New Zealand, would result in a similar outcome; and

- a proposal for rectifying the difficulties identified in Burton.

Purpose of Taxation

- There are many reasons for taxation primary of which is to raise revenue for governments in order to meet their expenditure needs. In Australia. taxation as a percent of GDP has risen sharply from Federation to present day. Since Federation there has also been significant tension between whether the states or the Federal Government should collect taxes.[1] This has ultimately resulted in a hybrid taxation system which can result in variances between the states and taxation treatments of transactions. As the taxation base has grown, so has the complexity of its legislation.

- An alternative purpose to revenue raising is the use of taxation to change behaviour through penalties or incentives. Taxation of tobacco or alcohol are examples of behaviour changing taxes whose primary purpose is to reduce consumption which have a disproportionate impact on those households with lower incomes compared to high income households. Penalties, for example speeding fines, are comparatively more severe to lower income households rather than higher income households. Its difficult to imagine that the government intended to make speeding or alcohol less attractive to low income households than high income households. This also represents a failure in taxation policy on the other hand implementing a more equitable system would be significantly harder to administer. Using taxation rather than making the behaviour illegal is also beneficial as it can reduce consumption without creating a black market and civil disobedience.

Why Double Taxation should be prevented

- The OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration defines double taxation as “the imposition of comparable taxes in two (or more) States on the same taxpayer in respect of the same subject matter and for identical periods[2].

- Double taxation represents a significant barrier to trade between countries as it deters individuals or companies of one country from investing in another country. Reducing barriers to trade is seen as generally beneficial to all parties. The prevention or reduction of double taxation is largely achieved through bilateral conventions. These bilateral conventions are influenced by the OECD Model Convention which is also used by non-OECD member countries when negotiating these conventions[3].

- Without preventing double taxation the benefit of international commerce can be partly or even completely eroded. For example, consider two countries who each tax an amount of income at 50%. In this case, the taxpayer would be paying the whole of his income in tax and there would be no remaining profit for the taxpayer. The taxpayer in this instance is likely to either avoid tax or not complete the transaction.

- Domestically double taxation may occur often and so many provisions within the Australian Tax system are designed reduce instances of double taxation. An example such a provision would be the allowance of Franking Credits in respect of tax paid on dividend income to shareholders.

- Preventing double taxation also makes taxation administration far simpler. Take the following example of two shareholders A and B. The government would like to tax companies at a flat 30%. The government would also like to tax shareholder A at twice the rate of shareholder B (because shareholder A can pay more therefore should pay more). Setting shareholder B’s tax rate at double that of A’s would result in the following:

- The company earns $100 and pays $30 in tax. It issues a dividend of $70 to shareholder “A” who is taxed at 50% – the after tax income is $35. The effective tax rate for shareholder A in this case is 65%;

- The company earns $100 and pays $30 in tax. It issues a dividend of $70 to shareholder “B” who is taxed at 25%; the after tax income is $52.5. The effective tax rate for the individual in this case is 47.5%

- Without credits for the taxation paid by the company, the government would need to set the taxation of each of A and B on a logarithmic scale with an included variable of the first taxpayer being the company. To achieve fairness in a system without franking credits would be extremely complex.

- In the example above, where the legislation provides Franking Credits for tax paid at the company level; the effective tax rate for Shareholder A will be 50% and for Shareholder B will be 25%.

- Whilst domestically in Australia the issue of double taxation has been largely prevented, internationally the various mechanisms that sovereign nations use to tax income and capital domestically are often incompatible with mechanisms used by other sovereign nations.

Capital Gains in the OECD Model Convention

- The OECD Countries have developed a model convention for countries to use as a standardised template when drafting their bilateral conventions[4]. The Article relating to the taxation of Capital reads as follows:

- Capital represented by immovable property referred to in Article 6, owned by a resident of a Contracting State and situated in the other Contracting State, may be taxed in that other State.

- Capital represented by movable property forming part of the business property of a permanent establishment which an enterprise of a Contracting State has in the other Contracting State may be taxed in that other State.

- Capital of an enterprise of a Contracting State that operates ships or aircraft in international traffic represented by such ships or aircraft, and by movable property pertaining to the operation of such ships or aircraft, shall be taxable only in that State.

- All other elements of capital of a resident of a Contracting State shall be taxable only in that State[5].

- The OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital, commentary on Article 22 concerning the taxation of capital[6] states at a paragraph 3:

- Taxes on capital generally constitute complementary taxation of income from capital. Consequently, taxes on a given element of capital can be levied, in principle, only by the State which is entitled to tax the income from this element of capital.

- The right to tax immovable property belongs to the state where the immovable property exists and the right to tax immovable property is ascribed to the location of the economic owner of that property. Where the economic owner can be ascribed to a permanent establishment, the country in which that permanent establishment is located will be country who has the right to tax the property.

Reservations

- The OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital[7] on page 374 and 375 set out the reservations of the subscribing countries to adopting the principles of the Article in full. Spain for example reserved its right to tax capital in certain circumstances relating to companies whose assets are mainly immovable property and are substantially resident in Spain. New Zealand, Portugal and Turkey all reserved their position on Article 22 if and when they impose taxes on Capital.

- Australia, despite having the opportunity, did not reserve its rights and as at 21 November 2017. The implication is that Australia consents to the foreign taxation in accordance with the principles set out in the convention.

Two Methods to Prevent Double Taxation

- The OECD Model Convention proposes two methods to reduce instances of double taxation. The exemption method and the credit method.

- The exemption method essentially exempts the amount of income or capital from taxation in a country if another country is entitled to tax that amount by virtue of one of the Articles in the convention.

- The credit method allows a credit to the taxpayer in respect of the tax paid in another country who by virtue of the one of the Articles the other country has an entitlement to tax that amount.

- In the event that the two countries are of the view that they are both, by virtue of an Article in the convention, entitled to tax the same amount the countries agree under most conventions to mutually agree on an outcome or refer the matter to the Council for Trade in Services.

- Australia has adopted the Credit method and section 770-10 of the ITAA 1997 provides for that credit to be applied on the amount of foreign income tax paid. However, in other cases Australia adopts the exemption method for example under section 23AH of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936, foreign branch income and foreign branch capital gains are usually exempt.

Failures of International Tax Policy

- The domestic and international framework also contains significant gaps where schemes are applied which artificially circumvent a country’s right to tax income which should, morally, be taxable in that country. Often these schemes work within the OCED’s adopted frameworks. The scheme referred to as the Double Irish Dutch Sandwich[8] is one of many such scheme intended to aggressively minimise tax which made up 60% of all global trade or $12.7 Trillion dollars in 2015 on which minimal tax was paid to any country. Australia has introduced a number of provisions to prevent multinationals in particular avoiding tax[9].

A Simple Test for Double Taxation

- For the purpose of this paper a taxpayer will be deemed to have been “double taxed” if:

- Two countries impose tax on the same amount of income; and

- The total tax paid in respect of that income is greater than the highest of the taxes that would have been imposed by either of the two countries.

Burton’s Case

- Burton was an Australian Tax resident who sold investments in the United States of America (US). Burton was subject to taxation in the US and Australia. Article 22(2) of the Convention[10] allows a credit to Australian tax residents in respect of income derived from sources in the US. Burton having held the investments for a period of more than one year was eligible for:

- US tax relief in the form of a discounted tax rate reduced from 35% to 15%; and

- The 50% CGT discount to the capital gain to be included in his Assessable Income.

- US tax years are calendar years whereas Australian tax years end on 30 June each year. Burton sold the investment in multiple lots which were spread over two US tax years but only over 1 Australian tax year.

- Mr Burton in the US:

- In the 2010 US tax Year:

- Sold assets worth USD$8,985,565;

- being a Long-Term Capital Gain was subject to a 15% tax rate on that amount; and

- Paid USD$1,347,834 in tax.

- In the 2011 US tax year:

- Sold assets worth USD$14,584,795;

- being a Long-Term Capital Gain was subject to a 15% tax rate on that amount; and

- Paid USD$2,187,720 in tax.

- In the 2010 US tax Year:

- Paid a total of USD$3,535,554 or AUD$3,414,207.

- Mr Burton in Australia:

- Triggered CGT Event A1 in the amount of AUD$22,754,321 pursuant to section 104-10 ITAA 1997 (CGT Event A1);

- Applied the 50% CGT Discount pursuant to section 115-25 ITAA 1997;

- Included $11,366.161 in his assessable income; and

- Paid AUD$5,114,772 in Australian taxes in the year ended 30 June 2011 tax year.

- Burton claimed a foreign income tax offset of AUD$3,414,207 being the USD$3,535,554 paid in US taxes under section 770-10(1) of the ITAA 1997 which reads:

- (1) You are entitled to a * tax offset for an income year for * foreign income tax. An amount of foreign income tax counts towards the tax offset for the year if you paid it in respect of an amount that is all or part of an amount included in your assessable income for the year.

- The Commissioner claimed that Mr Burton, pursuant to section 770-10 of the ITAA 1997, was only entitled to a tax offset on amounts included in his assessable income which was the amount of $11,366.161 being half the gain after the 50% CGT discount had been applied. In respect of that amount Mr Burton had only paid AUD$1,707,103.50 not the full amount of AUD$3,414,207 paid in respect of the whole capital gain[11]. The Federal Court agreed with the Commissioner that Mr Burton was only entitled to claim a tax offset of AUD$1,707,103.50.

Double Taxation of Burton

- Applying the simple test set I have set out,

- had Mr Burton sold an Australian asset in Australia he would have paid AUD$5,114,772 in Australian taxes in the year ended 30 June 2011 tax year giving him an effective tax rate of 22.47%;

- The actual total tax paid by Mr Burton on the transaction was AUD$3,414,207 plus AUD$5,114,772 less the allowed tax offset of AUD$1,707,103.50 equals total AUD$6,821,875.50 giving him an effective tax rate of 29.98%.

- The higher taxing country was Australia taxing in an amount of AUD$5,114,772 however the actual tax paid was AUD$6,821,875.50 therefore failing the test and resulting in a portion of double taxation.

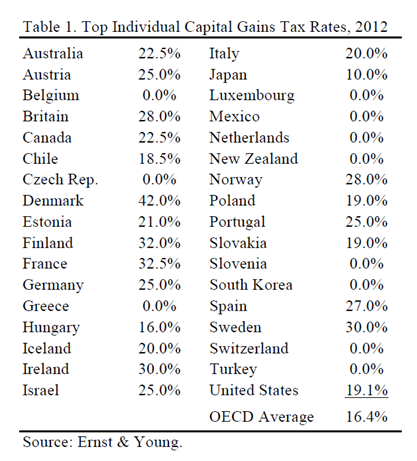

Reducing Capital Gains Tax

- In 2012 the OECD average capital gains tax was 16.4% and at that time the top individual capital gains tax rate in the US was 19.1%[12]. Burton at that time was taxed in the US at a rate of 15% however in Australia the rate of capital gains was much higher at 22.47% base level and after he was taxed twice the rate was 29.98%. Burton was taxed at almost twice the OECD average at that time.

- It is perhaps arguable that it is inequitable to tax capital gains on income producing assets at all. Income producing assets are prized for their ability to produce income. If the asset’s income rises then the value of the asset also rises, in Australia we tax both the value of the asset and its income.

- For example, consider a non-depreciating asset with a cost base of $100 that has derived income of $5 for the last 10 years. Taxed at the highest marginal tax rate, over the last 10 year period income tax paid would be $25 being 10 x $2.5. Imagine now that due to increased demand, the income producing capability increases to $10 a year. The value of the underlying asset would also increase as a result, with residential property for example if the rent yield doubled on a property so too would its value. The taxpayer now sells that asset for $200 making a gain of $100, after the 50% CGT discount and applying a 50% highest marginal tax rate the taxpayer will pay tax on the capital gain of $25 in that single income year. Looking at this asset over a 10-year life span the total tax payable in respect of that asset would be $50 and total income after tax would have $100 that’s a yield of 10% per year after tax.

- With the government now removing the 50% CGT discount for foreign investors, the tax would increase to $75 and profit would reduce to $75 over a 10 year period. That gives a yield of 7.5% per year after tax.

- The reserve bank of Australia’s inflation target is between 2 and 3 percent a year[14] (average 2.5%). The RBA meeting its target means that Australian resident have a yield of 7.5% and a foreign resident has a yield of 5%. In this example Australian residents have a 50% higher yield when compared with foreign residents.

- According to DataBank[15] in 2018 the amount Foreign direct investment, net inflows as a %of GDP was as follows:

- the world average was 1.391%;

- taking 5 OECD countries at random who taxed Capital gains above 20%:

- Australia was 4.2%;

- Spain was 3.5%

- France was 2.2%

- Sweden was 1.6%

- United Kingdom was 1.2%

- taking 5 OECD countries at random who taxed Capital gains at 0%:

- Mexico was 3.1%

- Czech Republic was 3.5%

- Greece was 1.8%

- Turkey was 1.7%

- New Zealand was 1.0%

- *Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg are all countries whose CGT rate is 0% but who all had rates of below -5%. I also note the types of countries mentioned above are not comparable countries.

- I would have also thought that by introducing a capital gains the foreign direct investment as % of GDP would have decreased. This does not appear to be the case.

- The scope of this paper does not extend to an in-depth analysis on the impact that Capital Gains tax has on foreign direct investment, but the conclusion I would make is that the rate of taxation does not appear to correlate with the level of foreign direct investment as a %of GDP.

Federal Court Decision

- It is my view there is an alternative interpretation to section 770-10 that the Federal Court may have taken, particularly in respect of the words “it in respect of an amount that is all or part of an amount included in your assessable income for the year” which I will now refer to as “the Words”. It was Burton’s 3rd and 4th pleadings which resulted in the analysis of the word “in respect of”. In my view the better ground would have been to draw the court’s attention to the words “or part of”.

- One of the unanimously endorsed principals of statutory interpretation is as follows:

- That the overall objective of statutory construction is to give effect to the purpose of Parliament as expressed in the text of the statutory provisions;[17]

- To my mind a question which the court did not consider in Burton was how to interpret the words “or part of an amount” in the context of this provision. Consideration of these words could have led to a better outcome.

- It is very difficult to discuss this matter without confusing the different “amounts” the Words could be referring to. There are two options which I will call X and Y:

- X = the amount included in your assessable income;

- Y = The proceeds of sale less its cost base (AUD$22,754,321);

- In Australia not all income is treated the same. Two usual types of income are known as

- Income according to ordinary concepts otherwise known as Ordinary Income as expressed under section 6-5 of the ITAA 1997; and

- Statutory Income which is defined income in the relevant tax acts as expressed under section 6-10 of the ITAA 1997.

- If an amount is not Ordinary Income it may be Statutory Income for example section 160ZO of the ITAA 1936 includes net capital gains in assessable income.

- Ordinary Income is included in your assessable income directly which can then be offset by deductions which are also included in your assessable income. Conversely only Net Statutory Income is included in your assessable income. This is after the operation of a number of provisions which will effect the amount which is included such as:

- Carry forward losses are applied;

- Small Business CGT Discounts are applied such as the 50% CGT Discount or Retirement Exemption; or

- Certain Rollovers may apply.

- Following the application of provisions to an amount Y, the amount X is then included in your Assessable Income. Under Australian law, X could never be “a part”. X is the final amount which is included. There is no further effect that X could be subject to in Assessable Income.

- Conversely, unlike an amount of X, an amount Y could be wholly or partly included in assessable income. The amount Y may not be reduced at all by any carry forward loss or may not be eligible for the 50% CGT discount. The amount X is a derivation of the amount Y.

- It goes against the grain of statutory interpretation, unless no other interpretation exists, that words do not have meaning if contained in statute. Given that there is an alternative interpretation of which amount the Words are referring to, the court could take the view that the Words refer to the amount Y not the amount X.

- However, if it was the case that Y is the amount referred to, then the words “included in your assessable income for the year” do no work in the provision, if it were not the case that some income is exempt income. Exempt Income is neither Ordinary Income nor Statutory Income and is not included in Assessable income. The provision, in my view, should on that interpretation be read as follows:

- (1) You are entitled to a * tax offset for an income year for * foreign income tax. An amount of foreign income tax counts towards the tax offset for the year if you paid it in respect of an amount of Ordinary or Statutory Income provided that the amount or part of that amount is included in your assessable income.

- The first sentence in 770-10 is a clear, concise and plain assertion that “if you paid foreign income tax then you are entitled to a tax offset”. In my view the second sentence is not intended to replace the plain meaning of first sentence but rather to add a qualification to it. If the Federal Court’s interpretation is applied then the first sentence becomes redundant. It is not required, all the work is performed in the second sentence. However, if the second sentence is a mere qualification then the qualification in my view is that the tax offset is not available for exempt income.

- Consider the following two examples:

- I will go to the park. However, if its raining I will take an umbrella;

- I will go to the park. If it is not raining I will go to the park but if it is raining then I will not go to the park.

- The first example includes a statement and qualification and the second includes a statement which is then completely negated under certain conditions. The sentence “I will go to the park” is always true in the first example, but in the second example the first sentence can be false.

- The Federal Court’s interpretation of the provision is akin to reading “If you paid foreign income tax then you are entitled to a tax offset… unless you aren’t entitled”. As stated in paragraph 37 above; making superfluous or redundant the first sentence in 770-10 surely cannot be the interpretation given the context of the whole. If the first sentence is to do work then the second sentence should be read as a qualification not as a negation.

- It is therefore my view, that it was open to the Federal Court to viewed the amount referred to as Y not X to which the taxpayer can gain a tax offset and in Burton’s case the amount is AUD$22,754,321 which then provide him with Foreign Income Tax Credits in the full amount of AUD$3,414,207.

- However, applying my interpretation, if Burton’s gain was $1,000,000 to which he paid $150,000.00 of tax in the US, then in Australia he applied the 50% CGT Discount to the amount followed by the $500,000 retirement exemption then there would be no amount included in his assessable income and he would not be entitled to a tax offset. However, if the amount of the gain was $1,000,001. Then after the 50% CGT discount and the retirement exemption $0.50 would be included in his assessable income. Assuming that he had sufficient other tax payable to absorb the credit Burton would be entitled to the tax offset of $150,000.

- This is a bizarre outcome.

- In Burton, Logan J in particular rejected the need to rely on the international tax treaty on the basis that the meaning of 770-10 was plain. I personally do not consider the meaning to be plain or evident and perhaps the intention of the tax treaty should have been given more weight. The Federal Court has previously looked to international law principles when considering how a tax treaty has been incorporated into Australian law. In Thiel v Commissioner of Taxation in McHugh J’s judgment[18]:

- The Agreement is a treaty and is to be interpreted in accordance with the rules of interpretation recognised by international lawyers: Shipping Corporation of India Ltd v Gamlen Chemical Co (A/Asia) Pty Ltd (1980) 147 CLR 142 at p 159. Those rules have now been codified by the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties to which Australia, but not Switzerland, is a party. Nevertheless, because the interpretation provisions of the Vienna Convention reflect the customary rules for the interpretation of treaties, it is proper to have regard to the terms of the Convention in interpreting the Agreement: even though Switzerland is not a party to that Convention: Fothergill v Monarch Airlines Ltd (1981) A.C. 251 at pp. 276, 282, 290; The Commonwealth v Tasmania (the Tasmanian Dam Case) (1983) 155 C.L.R. 1 at p. 222; Golder case (1975) 57 I.L.R. 201 at pp. 213-214..

- … [because the term enterprise is ambiguous] it is proper to have regard to any ‘supplementary means of interpretation’ in interpreting the Agreement. In this case the supplementary means of interpretation are the 1977 OECD Model Convention for the avoidance of Double Taxation with respect to Taxes on Income and Capital, which was the model for the Agreement and Commentaries issued by the OECD in relation to that model convention.

- The Commissioner sets out his view on the interpretation of treaties, (which seems not to be consistent with his argument in Burton) at paragraph 92 of TR 2001/13:

- the Vienna Convention rules apply to tax treaties just as for other treaties;

- reflecting the need for negotiating compromises, treaties are usually less precise than domestic legislation. Consequently, treaty interpretation should be based on a view that treaties cannot be applied with the ‘taut logical precision’ that might be appropriate for statutes. International instruments should therefore be interpreted more ‘liberally’ than domestic legislation;

- Article 31 of the Vienna Convention requires a ‘holistic’[19] approach to treaty interpretation – that is, a simultaneous examination of:

- the ‘ordinary meaning’ of the relevant words;

- their ‘context’; and

- the ‘object and purpose’ of the treaty they form part of;

Country Comparisons

- There are many different taxation systems employed by governments to raise revenue around the world. The taxation of income is fairly consistent being that any wages or salary earned by an individual is brought to tax usually under progressive escalating tax brackets. Conversely the approach to the treatment of capital gains is varied and diverging from complex systems such as Australia where capital gains are subject to separate rules with specific deductions that are then fed into its progressive income tax bracket system, to countries such as New Zealand who do not tax capital gains.

International Tax Treaties

- For the ease of understanding I will replace the facts in Burton with the following:

- All figures are in Australian dollars;a

- The sale price was $26,000,000 or $26M;

- Cost base was $2,00,000 or $2M;

- The gain was $24,000,000 or $24M;

- His marginal tax rate was 50% in Australia; and

- he has no carry forward losses.

Australia / Australia

- For the following section I will assume that US law has been completely replaced by Australian Law in the case of Burton to determine if double taxation would be prevented in a mirrored system.

- From 8 May 2012 as a foreign resident Burton would no longer be able to claim the 50% CGT discount in the US (the amount is apportioned if held before 8 May 2012) pursuant to section 115.110 of the ITAA 1997.

Example 1

- If Burton was not eligible for the 50% CGT Discount in the US:

- US Tax

- Burton would be assessed as a foreign resident in the US:

- the full gain of $24M would be included in his assessable income;

- At his marginal tax rate, he would pay $12M in US Tax; then

- Burton would be assessed as a foreign resident in the US:

- Australian Tax

- Burton would be assessed as a resident in Australia:

- The amount of $24M would be assessed as an A1 disposal;

- He would apply the 50% CGT discount

- The amount of $12M would be included in his assessable income;

- At his marginal tax rate, he would pay $6M in Australia.

- Burton would be assessed as a resident in Australia:

- US Tax

Example 2

- If Burton was eligible for the 50% CGT Discount in the US:

- US Tax

- Burton would be assessed as a foreign resident in the US:

- The amount of $24M would be assessed as an A1 disposal;

- He would apply the 50% CGT discount

- The amount of $12M would be included in his assessable income;

- At his marginal tax rate, he would pay $6M in US tax.

- Burton would be assessed as a foreign resident in the US:

- Australian Tax

- Burton would be assessed as a resident in Australia:

- The amount of $24M would be assessed as an A1 disposal;

- He would apply the 50% CGT discount

- The amount of $12M would be included in his assessable income;

- At his marginal tax rate, he would pay $6M.

- Burton would be assessed as a resident in Australia:

- US Tax

Application of Burton

Example 1

- In example 1 Burton would have paid $12M in US tax and then been liable to pay $6M in Australia he would be seeking to apply 770-10 to obtain a tax offset in the amount of foreign tax paid. Example 1 follows the same set of facts as in the case of Burton. In this example the $12M tax was paid on the gain of $24 million. Only half of that $24M was included in his assessable income and the court in Burton only allowed half the foreign tax paid to be applied as a tax offset. The court would only allow a credit of half the $12M to be applied against his assessable income of $6M (reducing it to 0).

- This example does not result in double taxation because the tax paid in US was double the amount payable in Australia. If the US tax was less than twice the Australian tax payable it would have resulted in double taxation according to the test set out in paragraph 11.

Example 2

- In example 2 he would have paid $6M in US tax and then being liable to pay $6M in Australia he would be seeking to apply 770-10 to obtain a tax offset in the amount of foreign tax paid. There are two possible outcomes from the application of section 770-10:

- The first interpretation is that the $6M in tax is paid on the $24M capital gain of which only $12M was included in his assessable income. Under Burton the amount of the tax offset would be reduced to $3M meaning that a total of $9M of tax is payable resulting in double taxation as set out in paragraph 11.

- The second interpretation is that the $6M in tax is paid on the $12M included in his US assessable income. Under Burton it is not at all clear how this would be viewed. The court would need to consider whether the $12M “amount” included in the US assessable income was the same or equivalent to the $12M “amount” that was included in Australian assessable income.

- Money is fungible meaning that it is a homogenous, non-distinct item with identical specifications. In Burton however and in the definition of 770-10 the concept of the fungibility of money is removed and this is unsurprising within our Australian taxation system. All income is not the same, different types of income are treated in different ways and subject to different rules than other income Ordinary Income, Statutory Income and Exempt Income are obvious examples. In these circumstances it is clear that an amount of income is distinct from another amount of income.

- The 50% CGT discount halves the proceeds of the CGT Event A1 which is held to be Statutory Income. Then half the amount is included in the assessable income of the taxpayer to which finally the taxpayer pays tax on. There exists a remaining half that was not subject to tax at all. In respect of the half that was not taxed, it could be argued that no foreign tax was paid in respect of that amount at all.

- The approach proposed by the Commissioner and adopted by the Federal Court in Burton was that the US tax paid of AUD$3,414,207 was in respect to the full amount of the sale proceeds of AUD$22,754,321. Later when the amount of AUD$22,754,321 was brought to tax in Australia the effect of the 50% CGT discount was to half the full amount and include a half in Burton’s assessable income. The court then apportioned the amount of the US tax which could be said to have been paid of the half, thereby halving the credit as well.

- In this example, the $6M was paid in respect of the $12M included in his assessable income and there remains $12M to which no tax has been applied. When the amounts are then assessed under Australian law the two halves are brought together again, fungibility would apply to make the two halves indistinguishable and attached now to the full $24M was the $6M in US tax paid. Once that amount is halved under the Australian tax system by virtue of the 50% CGT Discount, again the apportionment approach would be applied and only a tax offset of $3M could be said to be in respect of the $12M included in his Australian assessable income.

New Zealand

- New Zealand has no capital gains tax[20].

- As there would be no tax paid in New Zealand and all tax would be paid in Australia there would be no double taxation.

US Taxation of Capital Gains

- In the US capital assets are when a capital asset is sold for more than its purchase price (basis) the difference is subject to tax. If the asset is held for less than one year it is classified as a “short-term capital gain” and taxed as ordinary income at the taxpayer’s progressive rate. If an asset was held for more than one year it is classified as a “long-term capital gain”. Long-term capital gains are indexed to inflation and in the 2020 year are taxed at either 0%, 15% or 20% depending on the income tax bracket of the taxpayer. Long-term capital gains are not included in the assessable income of a US taxpayer. In addition to Federal Taxation, US states often also apply their own Capital Gains Tax which can vary between 0% to 13.3%[21].

- The taxation of capital gains from a foreign country is incredibly complex compared to the other countries I have considered. I understand that the capital gain will be included in the taxpayer’s income however depending on the tax rate of the foreign source income will depend to what extent that amount it reduced. For example if the foreign income was taxed at 15% then 40.54% of foreign sourced income will be disregarded from income taxation and if the foreign sourced income was taxed at 28% then the amount of the foreign sourced income which is included in the resident income tax for that year will be reduced by 75.68%.[22].

- The IRS Website states that:

- Foreign Tax Withheld and Income Tax Treaties

- The amount of foreign tax that qualifies as a credit is not necessarily the amount of tax withheld by the foreign country. If you are entitled to a reduced rate of foreign tax based on an income tax treaty between the United States and a foreign country, only that reduced tax qualifies for the credit. Amounts for which you are not legally liable (such as taxes in excess of the treaty rate) should be excluded from the amount reported in Part II.

- My understanding is that the US will separate a US citizens Foreign Earned Income from their US sourced income. There is also a “Maximum Foreign Earned Income Exclusion Amount” which in the 2019 year was $105,900 this amount will reduce your Foreign Earned Income.

- In the case of income, a credit will also be given for foreign tax paid on in the amount of income pursuant to set out in “26 USC 901: Taxes of foreign countries and of possessions of United States”. However the amount of the capital gain would not be considered as income and therefore would be allowed as a foreign tax credit for the capital gain.

- The US resident would then be taxed at their marginal tax rate.

- If Burton was a US resident with a gain in Australia he would be subject to double taxation on the gain as whilst the amount is reduced by the US apportionment method set out in paragraph 65 it does not give the taxpayer and equivalent deduction or credit.

Canada

- Canadian residents are taxed on their worldwide income. For residents, capital gains in Canada are reduced by 50% and the remaining amount is assessed as income. For non-residents Canada distinguishes property as Canadian Taxable Property and “Treaty Protected Property”. A foreign resident who sells Treaty-exempt property would be exempted from taxation in Canada[23].

- Canadian Taxable Property includes:

- real or immovable property situated in Canada

- property used or held in a business carried on in Canada[24].

- Canadian Residents are entitled to a foreign tax credit pursuant to section 126 of Canada’s Income Tax Act which states:

- 126 (1) A taxpayer who was resident in Canada at any time in a taxation year may deduct from the tax for the year otherwise payable under this Part by the taxpayer an amount equal to

- (a) such part of any non-business-income tax paid by the taxpayer for the year to the government of a country other than Canada (except, where the taxpayer is a corporation, any such tax or part thereof that may reasonably be regarded as having been paid by the taxpayer in respect of income from a share of the capital stock of a foreign affiliate of the taxpayer) as the taxpayer may claim,

- 126 (1) A taxpayer who was resident in Canada at any time in a taxation year may deduct from the tax for the year otherwise payable under this Part by the taxpayer an amount equal to

- The amount of the foreign tax credit is limited as follows:

- The maximum amount of each foreign tax credit that the taxpayer may claim with respect to either foreign non-business-income tax or business-income tax is essentially equal to the lesser of two amounts:

- the applicable foreign income or profits tax paid for the year; and

- the amount of Canadian tax otherwise payable for the year that pertains to the applicable foreign income

- The maximum amount of each foreign tax credit that the taxpayer may claim with respect to either foreign non-business-income tax or business-income tax is essentially equal to the lesser of two amounts:

- If the same facts in Burton applied but Burton was a resident in Australia with a gain in Canada he would be subject to double taxation on same basis as I have set out in paragraphs 55 to 61.

- If Burton was a Canadian resident with a gain in Australia in my view he would not be subject to double taxation on that amount by virtue of the Canadian provision which states that you get a deduction of an amount equal to the tax paid in a foreign country. The deduction is not made in respect of an amount which is assessed in Canada and so the interpretation of the court in Burton wouldn’t result in an apportionment despite the fact that Canada also gives essentially a 50% CGT Discount.

- The Canadian drafting of their tax credit provision should be preferred to the drafting of 770-10.

United Kingdom

- The United Kingdom taxes capital gains for individuals at a flat rate of either 18% or 28% depending on the individual’s tax bracket. Generally in the UK:

- The amount of credit for foreign tax is not to exceed the lesser of the foreign tax charged on the gain and the UK tax on the doubly taxed part of the gain.

- If the foreign tax paid exceeds the UK tax on the gain, the excess can neither be deducted from the amount of the gain chargeable to Capital Gains Tax nor can it be repaid.

- The amount of credit must be calculated separately for each gain. An excess of foreign tax over the UK tax on a particular gain can’t be credited against UK tax on any other gain[25].

- The section 18 Taxation (International and Other Provisions) Act 2010 (UK) provides for a deduction from income for foreign tax and states:

- Entitlement to credit for foreign tax reduces UK tax by amount of the credit

- (1)Subsection (2) applies if—

- (a)under double taxation arrangements, or

- (b)under unilateral relief arrangements for a territory outside the United Kingdom, credit is to be allowed against any income tax, corporation tax or capital gains tax chargeable in respect of any income or chargeable gain.

- (2)The amount of those taxes chargeable in respect of the income or gain is to be reduced by the amount of the credit.

- (3)In subsection (1) “credit”—

- (a)in relation to double taxation arrangements, means credit for tax payable under the law of the territory in relation to which the arrangements are made, and

- (b)in relation to unilateral relief arrangements for a territory outside the United Kingdom, means credit for tax payable under the law of that territory, but see sections 12(3) and 63(5) (dividends: certain tax payable otherwise than under the law of a territory treated as payable under that law).

- If the same facts in Burton applied but Burton was a resident in Australia with a gain in the United Kingdom he would be subject to double taxation on same basis as I have set out in paragraphs 55 to 61.

- If Burton was a resident of the United Kingdom with a gain in Australia then due to the flat tax rate of the United Kingdom the amount would not be subject to double taxation. However I note that section 18 of the Taxation (International and Other Provisions) Act 2010 (UK) uses the words “in respect of” in a similar context to section 770-10 of the income. In my view, if England had a 50% CGT discount applied prior to the flat tax rate, and the Federal Court of Australia was to interpret that provision then its likely that it would be subject to double taxation in the same way as section 770-10.

Carry Forward Losses

- This paper has not considered the use of carry forward losses in the consideration of Double Taxation. Carry forward losses are valuable in that they reduce the amount of a capital gain. It would be most beneficial to a taxpayer to apply foreign tax credits first before tax losses are applied thereby preserving the credits. Many countries such as Australia and the United Kingdom apply capital losses before foreign tax credits.

Proposed Amendment of 770-10

- To prevent double taxation in Australia and have regard to the manner in which other countries provide a discount the provision should be amended to read:

- If all or any part of an amount of income on which *foreign income tax has been paid is included in your assessable income for the year, you are entitled to a *tax offset to your assessable income in the full amount of the foreign income tax paid.

- The amount of the tax offset may not be used to offset any other amount of income included in your assessable income and may not result in a refund.

Imperative to Amend

- If it was intended or contemplated that section 770-10 was to be read in this way, then Australia would have made it clear to the other nations of the OECD that it intended to subject citizens of Australia to double taxation. The result would be to reduce the incentives for Australian citizens to invest overseas. There would be nothing wrong with this from a policy perspective however, I would expect that Australia would suffer significant pressure from other countries to change that policy. Given Australia representation that it would not subject its residents to double taxation when selling foreign assets the Australia should amend its position as soon as possible.

A Case for Change

- Burton was subject to double taxation. He paid AUD$3,414,207 in the US and was assessed at AUD$5,114,772 in Australia, only being eligible for a credit of half the US amount he paid a total of AUD$6,821,875.50 in tax to both the US and Australia. The tax payable was higher than the greater of either the US or Australian amounts.

- Double taxation on Capital amounts will not be limited to Burton or only between transactions with the US as set out in this paper. The court in Burton found that the interpretation of section 770-10 was “plain”[26] and that the tax treaty itself contemplated there would be differences[27] and therefore the did not need to be read in the context of the US Double Taxation Treaty. It is therefore not an error in the Tax Treaty which must be rectified but an error in section 770-10 which can easily be amended.

- We as a globe are a long ways off establishing an internationally uniform and consistent model of taxation. If we cannot move toward a global approach to taxation including dealing with multinational profit shifting then countries must act rapidly to patch any holes in their respective systems to achieve the agreed aims of the OECD. Being responsive to cases such as Burton is essential for an evolving system of international taxation. Further, countries should be striving to achieve uniformity in the interpretation of the many tax treaties.

- As Andrew Mills said “change in tax has been the one consistent feature of the tax landscape for decades”[28] it is time for Australia to amend section 770-10 of the ITAA 1997.

[1] Australian government. A brief history of Australia’s tax system. [Online]. [13 May 2020]. Available from: https://treasury.gov.au/publication/economic-roundup-winter-2006/a-brief-history-of-australias-tax-system

[2] OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2017-en.p4

[3] OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2017-en.

[4] OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2017-en.

[5] OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2017-en.

[6] OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2017-en.Publishing p.375

[7] OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2017-en.

[8] Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sep 4, 2016, International tax avoidance: the double Irish Dutch sandwich, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66ha_vhSJD0 accessed 08 May 2020.

[9] See Tax Laws Amendment (Combating Multinational Tax Avoidance) Bill 2015 (Cth), and Treasury Laws Amendment (Combating Multinational Tax Avoidance) Bill 2017 (Cth).

[10] Article 22, Double Taxation Taxes on Income Convention Between the United States of America and Australia signed at Sydney August 6, 1982.

[11] Burton v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCAFC 141, per Logan J paragraph 4

[12] Corporate Dividend and Capital Gains Taxation: A Comparison of Sweden to Other Member Nations of the OECD and EU, and BRIC Countries,” Ernst & Young, October 2012.

[13] Corporate Dividend and Capital Gains Taxation: A Comparison of Sweden to Other Member Nations of the OECD and EU, and BRIC Countries,” Ernst & Young, October 2012

[14] Matthew Cranston, (5 November 2019), Treasurer leaves RBA’s inflation target intact, Published by the Australian Financial Review, accessed 13 May 2020.

[15] https://data.worldbank.org/

[16] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?locations=AU

[17] See, eg, Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 355, 381 [69] (McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). Cf Justice Michael Kirby, ‘Towards a Grand Theory of Interpretation: The Case of Statutes and Contracts’ (2003) 24 Statute Law Review 95, 99.

[18] [1990] HCA 37 (Thiel); 90 ATC 4717.

[19] Lamesa (Full Federal Court, citing McHugh J in Applicant A v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs [1997] HCA 4 at [78]

[20] OECD(2017, Model tax Convention on Income and Capital: Condensed Version 2017, OECD Publishing

[21] Jared Walczak, Scott Drenkard, and Joseph Bishop-Henchman, 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index, Tax Foundation, Sept. 26, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/state-business-tax-climate-index/.

[22] https://www.irs.gov/individuals/international-taxpayers/foreign-tax-credit-compliance-tips

[23] Canada revenue agency. 2019-02-12. Disposing of or acquiring certain Canadian property. [Online]. [11 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/international-non-residents/information-been-moved/disposing-acquiring-certain-canadian-property.html

[24] Canada revenue agency. 2019-02-12. Disposing of or acquiring certain Canadian property. [Online]. [11 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/international-non-residents/information-been-moved/disposing-acquiring-certain-canadian-property.html

[25] HM Revenue & Customs. 10 July 2019. HS261 Foreign Tax Credit Relief: Capital Gains (2018) . [Online]. [10 May 2020]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/foreign-tax-credit-relief-capital-gains-hs261-self-assessment-helpsheet/hs261-foreign-tax-credit-relief-capital-gains-2018

[26] Burton v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCAFC 141, para .93

[27] Burton v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCAFC 141, para 169

[28] Andrew Mills, ‘Tax in a Changing World’ (Paper presented at the Australasian Tax Teacher’s Association 31st annual conference, Perth, 17 January 2019)

Leave a Comment Cancel Comment

Search

Latest Post

-

Narumon Pty Ltd (2018) QSC 185

March 1, 2022

Narumon Pty Ltd (2018) QSC 185

March 1, 2022

-

Munro v Munro [2015] QSC 61

March 1, 2022

Munro v Munro [2015] QSC 61

March 1, 2022

-

Ioppolo v Conti [2013] WASC 389

March 1, 2022

Ioppolo v Conti [2013] WASC 389

March 1, 2022

Most Commented

-

COVID-19 Business Hardship Grant

5 Comments

COVID-19 Business Hardship Grant

5 Comments

-

Trust Basics

4 Comments

Trust Basics

4 Comments

-

7 Things you need in your Standard Terms of Trade

2 Comments

7 Things you need in your Standard Terms of Trade

2 Comments

Categories

- Articles (16)

- Uncategorized (13)

Popular Tags

Archives

- March 2024 (2)

- May 2023 (2)

- March 2022 (6)

- February 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (5)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (2)

Comments

Your posts in this blog really shine! Glad to gain some new insights, which I happen to also cover on my page. Feel free to […] More...Your posts in this blog really shine! Glad to gain some new insights, which I happen to also cover on my page. Feel free to visit my webpage 81N about Cosmetics and any tip from you will be much apreciated. Less...